“I feel like people have a misconception of what research looks like. Research is anything where you’re trying to gather knowledge to advance a field. That’s what all the humanities students are doing here at Rice.”

Alison Drileck ’21

Sid Richardson College

Double major: History and Social Policy Analysis

Minor: Politics, Law and Social Thought

Co-Editor-in-Chief, Rice Historical Review

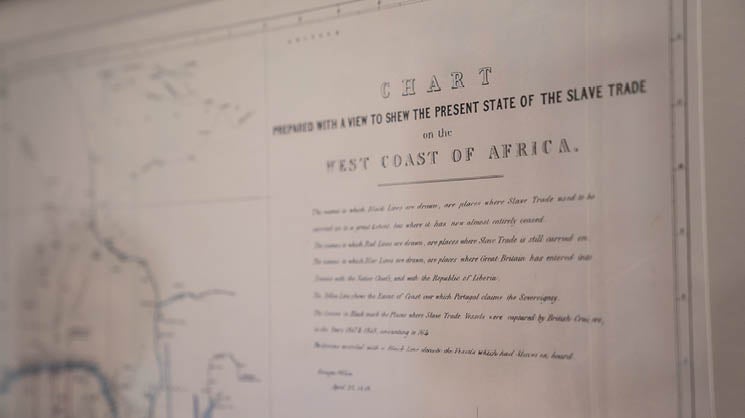

Rice University junior Alison Drileck is conducting essential research for the advancement of Slave Voyages, an online resource dedicated to exploring the African diaspora and slave trading across the Atlantic world. Drileck works under the guidance of Assistant Professor of African History Daniel Domingues, who has diligently worked on the Slave Voyages site for the past 18 years and has been a major contributor to the site’s Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, which houses over 36,000 records of voyages.

The Intra-American Slave Trade Database was added to Slave Voyages when the site relaunched earlier this year. It is the focus of Drileck’s research as she aims to populate it with information on voyages that sailed within the Americas. “Right now, I’m looking at newspapers published from 1825 to 1850 in Pernambuco, Brazil,” says Drileck. “I’m cataloguing all the ships leaving Brazil, noting how many ships were actually carrying slaves within the intra-American slave trade.”

“In the intra-American database, you can look for itineraries, place of departure, purchase, places of landing. You can select Brazil and right now Pernambuco doesn’t have anything except for just one record,” says Domingues as he clicks through the website. “But Alison’s work is going to change that.”

Drileck's work to construct a more comprehensive understanding of the slave trade coincides with the 400th anniversary of the initial arrival of enslaved Africans in what would become the United States.

“When you think about the trans-Atlantic slave trade, you think of these big ships that are absolutely packed full,” says Drileck. “But in the intra-American slave trade, the ships have a much smaller number of slaves — for example, eight crew and four enslaved individuals.”

“You sometimes have to take a step back,” she says, “because when you’re going through and entering things into the database, you can get disconnected from what this actually looked like and what it actually means.”

On the significance of Alison’s research, Domingues adds that people often think the journey for enslaved Africans ended once they reached the Americas. “That is not true at all, as we’ve seen by looking at the information that Alison is gathering,” he says. “They were actually transferred to even more distant places.

“It’s shocking when you see it,” he says. “It’s like a second Middle Passage of even greater distances.”