‘Sweet Taste of Liberty’: How a former slave fought for and won her day in court

Rice professor’s newest book shows historic connections between slavery and convict labor

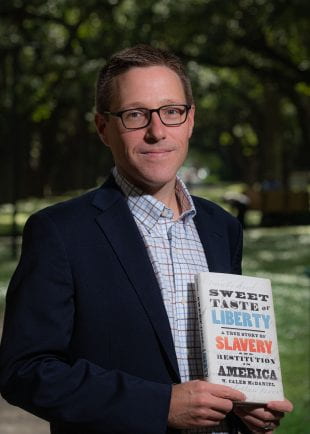

HOUSTON – (Aug. 30, 2019) – A new book from Rice history professor Caleb McDaniel presents the previously little-known story of Henrietta Wood, who survived enslavement twice and, 30 years after she was first freed, won the largest known financial settlement awarded by a U.S. court in restitution for slavery.

But McDaniel doesn’t stop there. Employing recent scholarship and years of research, “Sweet Taste of Liberty: A True Story of Slavery and Restitution in America” (Oxford University Press, $27.95) proves the connections between slavery and the convict labor system that arose after the Civil War.

McDaniel will kick off a 13-city book tour with a reading from “Sweet Taste of Liberty” Sept. 6 at 6:30 p.m. at Brazos Bookstore, 2421 Bissonnet St.

Prison leasing arrangements across the country, including those of the notorious Imperial State Prison Farm in Sugar Land, Texas, continued to impoverish and incarcerate black men and women until the arrangements were ended in the 1920s.

McDaniel said Wood’s successful lawsuit — she won $2,500 from Zebulon Ward, one of the men who enslaved her — demonstrates that African Americans fought from the beginning for redress and reparations. Despite recent attention drawn to the topic by U.S. House Judiciary Committee hearings this year during Juneteenth and Ta-Nehisi Coates’ award-winning “Case for Reparations,” which still resonates five years later, this is not a new conversation.

With the first book about Wood and the impact of her lawsuit, McDaniel is expanding that dialogue. He said the $2,500 helped Wood’s son, Arthur H. Simms, attend what would become Northwestern University’s law school.

“When it comes to questions surrounding reparations today, there’s a fair question to be asked whether any amount of money could matter or make a difference,” McDaniel said. “Here’s a story that shows the difference even a small amount of restitution can make in a particular person and family’s life.”

Wood was one of the estimated 150,000 enslaved people brought to Texas during the Civil War by planters seeking to avoid the Emancipation Proclamation. This followed a five-year period during which she had been given her freedom papers and lived as a free woman in Cincinnati — where, she later recalled, she’d had her first “sweet taste of liberty” — before being kidnapped and forcibly enslaved once again in 1853.

“It’s such an amazing story and I was amazed that I had not heard of it before,” he said.

Wood’s own words, woven throughout the book, bring her story to life. Historians of slavery are always looking for ways to overcome the neglectful or inhumane ways in which the lives of enslaved people were recorded by others — sometimes only as a number or a given name that wasn’t their own.

“In this case we have a narrative that Henrietta Wood herself was able to share, so we have at least some sense of how she wanted her story to be told and which parts of her life were important for her to emphasize,” McDaniel said.

“This book wouldn’t have happened without her determination to tell her story.”